Introduction - Historical Guide

Welcome to the online guide of Pariana.

We want to fully convey to those who visit Pariana, or even just see it on Google Maps while browsing via satellite, the deep identity of this village in the Lucchese mountains, through texts, images, impressions, and inspirations.

How can one understand the history of a village?

You understand it by grasping the basic, fundamental aspects of the role that community played in its territory — understanding “territory” as that vast Italian area that was constantly influenced by the city that inspired and shaped not only the plains but also the mountains: Lucca.

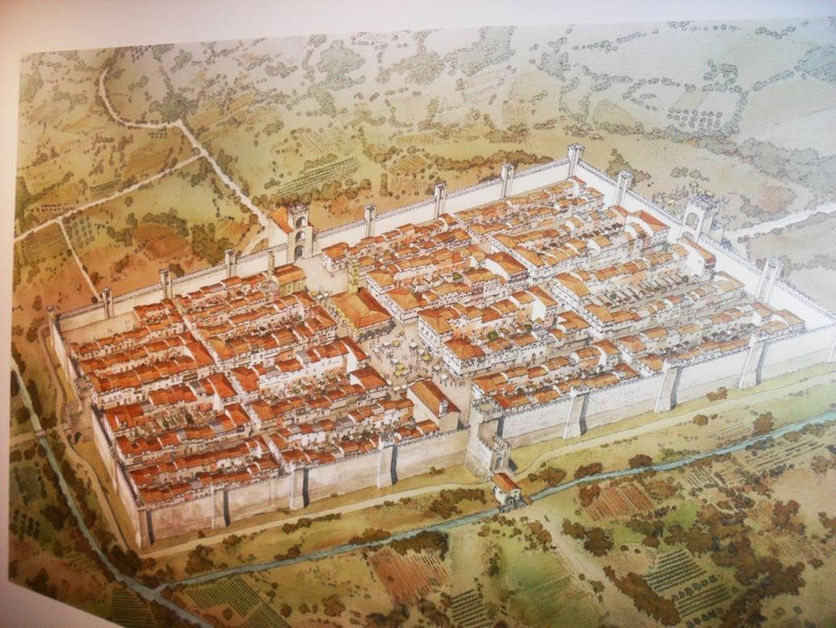

Of course, there is an older history, but we believe the story should start from when Pariana developed as a castle, a church, and a village — that is, from the Middle Ages, when it appears — I venture to say — as a terra nuova (new land). These terrae novae were lands that a city-state like Lucca, Pisa, or Florence created from scratch (or expanded from small pre-existing settlements), mainly to establish fortified outposts — especially near borders — and structures useful for their economy. At that time, Lucca was the center of Tuscany.

From the 12th to the 15th century, Lucca was the political, economic, social, and cultural beacon for its countryside and its mountains. Its power was based on the wealth generated mainly by the growth of a productive activity that the city initiated and developed at a certain point in its history: silk production. That fabric, along with everything connected to it, was the turning point.

Lucca became a world power, connected from the Far East and North African coasts (where raw silk came from) to the cities of the West, whose kings, cardinals, bishops, prelates, nobles, and wealthy bourgeois longed to dress in silk, the new marvel. Thus, Lucca’s producers, weavers, dyers, and others created entrepreneurial companies (the most famous being the Societas Ricciardorum, founded by Ricciardo, a simple dyer) that became so wealthy they were able to finance the kings of France, England, Spain, the Vatican, and Curias across Europe.

This led Lucchese merchants to settle in every major trading city in Europe — from London, to Paris, Bruges, Genoa, Venice — creating quarters dedicated to Santa Croce and the Volto Santo, their main symbol. It was an astonishing network that transformed the entire region, connecting the Tuscan cities of Lucca and Florence to the Tyrrhenian Sea, Pisa, Genoa, and the cities of the Po Valley — Parma, Reggio Emilia, Modena, Bologna, Mantua, Milan, Venice.

The silk production system spread throughout the territory via an organizational model in which the large producing families of the city outsourced the weaving to hundreds, even thousands of women, mainly scattered across the countryside and the Lucchese mountains, thus generating widespread wealth in the territory.

The practice of relocating activities to the mountains was widespread, especially where the mountains offered labor or energy resources that the city and the plains lacked. In addition to silk and textile production, another extremely important activity was the primary processing of iron ore, which in the area of Pariana and Villa Basilica also led to the unique specialization in the production of swords, knives, and cutting weapons. Most of the work involved smelting iron and producing semi-finished goods, which would then return to the urban artisan workshops and forges.

This was possible because the mountains were rich in forests for producing charcoal and had steep streams that provided hydraulic energy to power the hammers. The same reasons also led to the local development of paper production along the Pescia River, an activity that still characterizes the area today.

Moreover, there was the movement and processing of limestone to build kilns and lime furnaces, heavily demanded during phases of urban expansion. For the same reason, mountain quarries were opened (in places like Pietrabuona — a very telling name — Matraia, Vellano, Calamecca, and also in Pariana), where significant outcrops of sandstone provided materials and skilled stonemasons like the Calamech family of Calamecca, later active in Carrara and Messina.

And there was more: charcoal production, firewood for heating and urban crafts, fir trees for making oars, ship masts, and other naval construction elements. The city also needed leather for making shoes, belts, pulleys, and furs.

Most importantly, there was a constant demand from the city for agricultural products from the countryside and mountains to feed the urban population — large daily supplies of wheat, meat, cheese, vegetables, and more. Pastoralism also led to seasonal movements with transhumance routes that heavily used the Via di Pizzorna and the Lucchese and Pistoian mountains, as well as partnerships (soccide) for pasturing livestock.

It’s clear that all these activities gave the mountains a central, productive role — far more important than we might perceive today, in a time when local communities are facing depopulation and job scarcity. It was a different world.

Furthermore, this intense trade activity required the movement of goods, pack animals (especially mules), and vetturali — men who guided mule caravans along the mulattiere (mule tracks, so named for obvious reasons). The movement of goods demanded lodging and shelter structures every night — hospitality areas and caravanserais (walled spaces to house goods, animals, and people) were needed approximately every 25 kilometers, the average distance of a day’s travel.

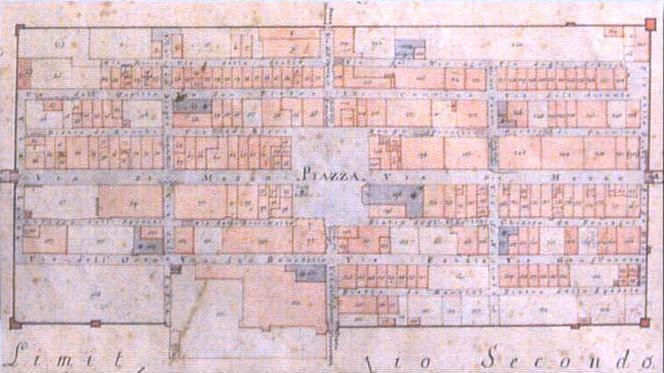

Pariana appears to be exactly this: a terra nuova, a caravanserai between the Lucca plain, Pistoia, Florence, the Ponte della Maddalena at Borgo a Mozzano, and the passes of the Pistoian mountains. Its urban layout reveals this clearly: a regular quadrangular shape, with four (or two) perpendicular streets leading to gates, enclosed by walls, with a central square and fountain.

Below, we will explore Pariana and other terrae novae under various dominations, Lucchese or Florentine…

Thus, it should come as no surprise that E. Bratchell, in his Medieval Lucca, highlights the leading role of the territory of the plebanate of Villa Basilica, to which Pariana always belonged, and of the Vicariate, again centered in Villa, which — as usual — also included Pariana.

Bratchell was able to make this observation because the territory of Pariana, and the village itself, found themselves, at various points in history, along a major route for the movement of goods, a system in which Pariana played a functional role. In the vast and complex transportation and shelter network that supported the economies of Lucca — and later Florence — the locations identified as stopover points were considered particularly fortunate, as this meant much greater wealth compared to other communities.

However, to prove that Pariana was indeed a functional locality within a transit route, it is necessary to demonstrate the existence of a strategic and important road.