Pariana, Comune and New Land of Lucca

The great attention that the government of Lucca gave over the centuries to the Plebanate of Villa Basilica testifies to its strategic importance, especially in the economic field. The fact that a bourgeois of Lucca, Grandonio, was invested with the governance of those lands indicates its role. And further proof is the effort to recover those lands by wresting them from the Empire. The opportunity arose in 1204, when, after the death of Henry VI, the Podestà of Lucca, Inghirame da Montemagno, quickly returned Villa Basilica, Pariana, Boveglio, and Colognora – in terms of property, men, rights, and income – to the Bishop of Lucca, before the new Emperor could claim those places as his own, based on the right we have seen represented in the various Diplomas.

AAL, 1194, Part of the Diploma of Emperor Henry VI to the Bishop of Lucca confirming possession of the Pieve of Villa Basilica with all its lands, including Pariana.

Five years later, in 1209, Emperor Otto IV, from Foligno, on November 16, renews the grants to the Bishop that had already been made before him by Henry IV and V, up to Lothair III, namely the Pieve di Villa Baxilica et totam eandem terram, cum fodro, et villis ad eam pertinentibus eodem modo ad justitiam faciendam.

Among the lands mentioned, outside the Plebanate of Villa, there was also Petrabola, that is, Pietrobana, and this indicates the stone quarrying activities, widely spread throughout the territory – in Matraia, Vellano, Calamecca, Pietrabona – since the Pizzorne area is rich in sandstone veins (the same used for Romanesque churches and extensively employed in the development of Lucca).

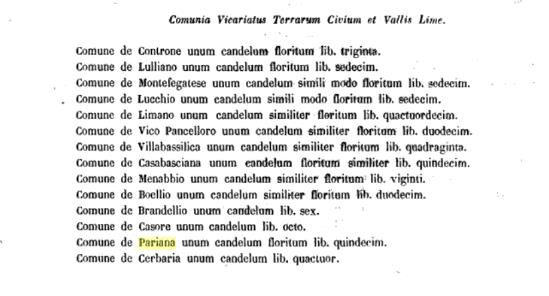

The thirteenth century, therefore, is a strategic century for Lucca. Its thriving industry required very strict control over the territory and especially over those areas that served as roads. We see this in the Garfagnana, which became peaceful and was conquered, and for half a century lived in peace, favoring the development of business. In this context, Lucca created the Vicariate of Camporgiano. Something similar may have happened also for Pariana, a stronghold on the Strada di Pizzorna. An operation that was completed in the 1240s, when Lucchese trade had become tumultuous and Lucca was, in fact, the economic capital of Tuscany.

The Diploma of Otto IV is a sign of a transition in which Lucca seeks to gain control of the territories, removing it from various lords – such as the Gherardinghi in Garfagnana and the Porcaresi, Corvaia, and Vallecchia in Versilia. In this phase, we see an action of reorganization of the territories dependent on Lucca, such as Garfagnana and the Lucchese mountain region.

But in this operation, it is the Comune of Lucca that must take on the role of territorial government, taking it from those who had held it by imperial concession for several centuries, namely the Bishop. The process, however, appears to be painless. In 1239 it appears that Villa Basilica and its Plebanate were no longer part of the Diocese but fell under the jurisdiction of the Comune of Lucca, and since there were no protests from the Bishop against possible usurpations by the Comune, it would appear that the transition occurred peacefully – probably through money, the principal instrument of Lucchese conquest.

This is explained by G. Tommasi, in his Sommario della Storia di Lucca:

If in every age the Comune (of Lucca, my note) strongly endeavored to draw to itself, by force or by the effective lure of money, the jurisdictions of the rural petty lords, it did so even more after the death of the second Frederick. But with ecclesiastics, it proceeded in quite a different manner: their properties, lordships, and privileges were considered untouchable: the government had to swear periodically, according to the cited Gregorian bull of absolution of 1137, not only to respect them but to make others respect them as well. If this oath indeed fell into disuse, as it seems, the present year provides us with sure proof of the government’s good disposition in maintaining clerical prerogatives. For, at the request of a papal legate, the bishop, and all the clergy, the General Council renewed the promises already made to Gregory IX. But since we are certain that in this very year the Plebanate of Villa Basilica was subject to the jurisdiction of the Comune; and since, from a certain point in the 13th century onward, acts of episcopal sovereignty over those lands are missing, as are complaints against the Republic for having appropriated them; and since, on the other hand, it appears that as early as 1239, the bishop obtained the faculty to alienate possessions and the homage of men who were more a burden than a benefit: thus, to reconcile all these facts, we must conclude that there was a voluntary cession on one side, and a purchase of dominion over Villa on the other. Which, detached from the other feudal possessions of the bishop’s jurisdiction, could bring little or no benefit to the prelate, who still had to maintain officials and troops there from his own resources; thus it entered precisely into the number of those burdensome homages to the episcopal table, and therefore alienable.

The operation by the Comune of Lucca to obtain from the Bishop, through money (a purchase, a common model in the 13th century), episcopal lands seems to have been successful especially with Villa Basilica and its district (i.e., Pariana and other lands), because, due to the opposition of the Canons of Lucca, as Tommasi further explains, the Comune of Lucca was prevented from using it as a model for other lands and castles.

G. TOMMASI, Summary of the History of Lucca

Likewise, the operation to detach Villa Basilica and its district from the lands that the Empire claimed as its own was successful, reassigning them left and right through Diplomas (Frederick II confirmed it in 1242). And, Tommasi further says, this operation intensified after the death of the Emperor himself, in the mid-13th century.

The transfer of the district of Villa Basilica – and within it Pariana – to the Comune of Lucca likely marked a turning point in the history of the latter. Pariana was directly involved, not only by assuming a new role but probably undergoing an urban transformation and being rebuilt as a Terra Nuova. In the two following documents, the existence of the Comune of Pariana is referenced, equipped with its own Podestà, a Lucchese citizen, Rocchesiano.

In the 1258 document, the government of Lucca – which, let us not forget, for centuries was composed of merchants, bankers, and bourgeois – acknowledges the merit and loyalty of the Comune of Pariana for having provided its due share to maintain and build some of Lucca’s fortresses. And, as a consequence, it is also decided to entrust the Comune of Pariana with the governance of Pariana itself, just as Lucca had governed it.

ASL, DIPLOMATICO, TARPEA, 1258. THE COMUNE OF PARIANA IS REFERENCED.

ASL, DIPLOMATICO, TARPEA, 13th CENTURY, ROCCHESIANO PODESTÀ OF PARIANA

It is a fundamental act of granting autonomy, typical of what Lucca did with the already mentioned Terre nuove. That is, places built from scratch, even in border areas, and fortified with castles and strongholds where new inhabitants could be brought and a secure stronghold established – also in the economic sphere: and we have spoken of the road function of Pariana. F. Redi, in his La frontiera lucchese nel Medioevo, refers to the urban layout of Pariana as a terra nuova.

Certainly, as mentioned, in this phase we also witness the relocation of the village from around the Church of San Martino and Lorenzo (as it is cited in 1260) to the plateau where it currently stands. Perhaps even the hydrogeological and seismic conditions – quite negative for the original village – may have suggested the move. However, Pariana was enclosed by walls, and the important testimony of the Porta Pizzorna remains, which from then on became a key point in the road network toward the north. F. Redi again notes that the village must have had three other gates: one to the south toward Pescia, and two lateral ones at the intersection of roads that converge in the central square, one of which certainly had to lead to the Church and continue on toward the Pistoiese mountains.

The existence of the autonomous Comune and Podesteria of Pariana marks the assumption of greater independence from Villa Basilica, which nonetheless remains the seat of the Lucchese Vicariate and of the Pieve in the religious sphere.

The Tithes of 1260 for the Diocese of Lucca still show the original situation of the Plebanate of Villa Basilica, which remains limited to the Churches of S. Martino and Lorenzo of Pariana, San Michele of Colognora, S. Ginese of Boveglio, and the appearance of the hospice of San Giovanni of Villa Basilica.

D. BARSOCCHINI, MEMORIES AND DOCUMENTS TO SERVE THE HISTORY OF THE DUCHY OF LUCCA

It should be noted how widespread the hospices were in the territory: in addition to this one of San Giovanni, possibly linked to the Knights Hospitaller known as of Malta, others are mentioned in history at Colognora, Boveglio, Corsagna. In Pariana there must have been, in 1416, probably a hospice dedicated to St. Bartholomew, as Domenico Pacchi writes.

The road function, as an area of passage, as mentioned, was emphasized during the phase of Lucchese trade expansion, especially after the death of Frederick II (1250) and the establishment of the Podesteria of Pariana. The territorial district of Villa Basilica, with its villages, becomes central to trade until the 15th century and beyond. Pariana was now a new village, equipped with walls and gates, and it is entirely plausible that it also had a fortress. The road is mentioned shortly thereafter – in 1429 – by Rinaldo degli Albizzi, who calls it the Via di Sopra and describes it as follows:

Villa Basilica always had close ties with the neighboring Lucchese vicariate of Valdilima. Wine and chestnut flour were exported from Villa Basilica; pigs moved in and out of the territory of Villa Basilica from Menabbio; sheep passed between Villa Basilica and Corsagna; cheeses and walnuts were brought from Lucchio; panni albagi were distributed from Villa Basilica to all the municipalities of Valdilima. (p. 190). And further:

To the south, through Corsagna, goods and animals passed to Villa Basilica, Collodi, and then to Pescia (and the entire Valdinievole), Pistoia, and Florence (p. 191). We are therefore in a context of great interest. The “goods” being referred to now are iron, silk, cloth, pigs and sheep, paper, lime, charcoal, building stone, leather and hides, and many food products (chestnut flour, cheeses, etc.). A great economic movement that generated wealth through the work of artisans’ workshops, farmers, woodcutters and charcoal burners, quarrymen, innkeepers and tavern owners, and notaries to draw up sales contracts.