The Mountain of Pariana and Its Activities

However, the mountain is not always peaceful, and the city’s conflicts often spill beyond the walls, frequently taking as their pretext the opposition between Guelphs and Ghibellines, Whites and Blacks, or, as in the 16th century, between “Italians and French,” as Ludovico Ariosto wrote in his Letters to the Duke of Modena. And from the letters of Guinigi, we also have information about unrest caused by groups who, fighting for control over the transit and economic activities flourishing in the mountains, often came to arms.

Thus, in 1413 we learn of an internal conflict in Pariana, where some exiles – probably banished by the Comune of Pariana – wandered the mountains armed. The name of Piero Bartoli and his seven companions is mentioned (an armed band like the many Ariosto knew, such as the bandits of Garfagnana).

A group of delinquent Pariani, child murderers and guilty of other crimes, roamed undisturbed in Pescia and the surrounding areas and, as Giovanni da Milano writes from Pariana, they perhaps intended to burn down the Castle of Pariana. E. Bratchell also mentions (ASL Capitano del contado, 31) these seditious individuals, giving their number as 8.

But later it is noted that perhaps they were not exiles from Pariana, but rather non-residents. However, the situation is clearly disorderly, as was the case in the neighboring Garfagnana of Ariosto. Yet, we cannot interpret these events except within the context of a dynamic society—even in the mountains—and one rich in money as well as in opportunities to make a fortune. From this comes the development of local powers who—being present in the area, managers of hospitality, providers of transport—locally controlled trade. Without the role and support of these leading classes of the local villages, the logistics of commerce would not have been possible.

On the other hand, the scale of productive activity and transit in the area of Villa Basilica and Pariana is truly exceptional—an exception. M. E. Bratchell, along with P. Pelù, emphasized how it was above all due to silk—which was the most valuable and prestigious product—that this scale of business existed. The letters provide a snapshot of local life in the early 1400s, which continued undisturbed despite some gruesome events, also giving us the names of some prominent Pariani figures such as Giovanni Massei, Ciomeo di Bonaiuti, Giovanni di Bonanno, Arrigo Doni, Bartolomeo Chelli, Biagio Bonansegna, Antonio Arrighi, Nicolao Massenti, and the already mentioned Piero Bartoli.

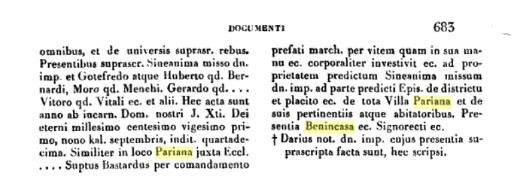

But above all, the figure of Bartolomeo Benincasa stands out, who played a central role in silk production and trade between the late 14th and 15th centuries, and who even appears to have been a member of a Pariani family already present in 1121, as stated in the document below:

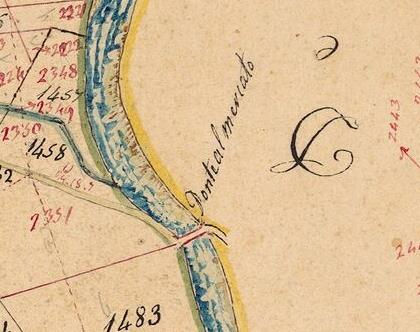

These are the names of wealthy, landowning families from this community who, by virtue of their wealth, built houses, towers, and palaces and held positions of power within the community and its magistracies (offices of authority), including the figures of the parish priest, the doctor, and the notary. A productive and commercial activity clearly symbolized in the toponym Ponte del Mercato, a crossroads where roads from Lucchese and Florentine lands converged.

CASTORE, NEW LAND REGISTRY OF LUCCA, PONTE AL MERCATO

The image of Siena in The Good Government by Ambrogio Lorenzetti, though different in scale – there a city, here a mountain – illustrates this active and lively world of trade, labor, human interactions, and relationships, both inside and outside the walls, in a vital osmosis between countryside and city, absolutely necessary for both.