The Pizzorne in the territory of Pariana.

The Pescia River border, Lucca, and the Plebanate of Villa Basilica (Pariana, Boveglio, Colognora, Villa).

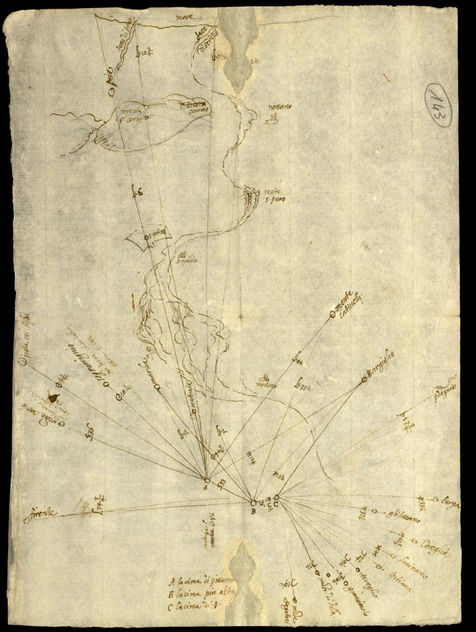

The Pizzorne Plateau has always been strategic for historical routes, both for Lucca and Florence, which fought for centuries over control of this area along the Pescia River — and here was Pariana, serving the Pizzorne. Below, the Lucca map shows what could be seen from the “Cima di Pizzorna” marked with “A,” and the “highest peak” marked with “B.”

From this elevated point, the entire valley, the plain below, the Apennines, and the cities could be seen in every direction, all the way to the sea (from Monte di Villa and Granaiola to Barga, to the mouth of the Arno and Serchio rivers, to Pisa, Segromigno, and even Florence). This position gave control over a territory located on a strategic border, always represented by the Pescia River, and this role as a border village would influence all of Pariana’s history.

It was during the Middle Ages that this territory developed, as evidenced by the richness and quality of its churches and parish churches, which reflect the particular vitality of the Bishops of Lucca. The Romanesque Church of San Martino (and later of San Bartolomeo and San Lorenzo), the Parish Church of Santa Maria Assunta in Villa Basilica, the “Parish Church” of San Jacopo e Ginese in Boveglio, and the Church of San Michele in Colognora all show a high level of Romanesque art and architecture, testifying to the importance of the area.

On this topic, an important point must be made immediately. The four churches and localities mentioned have undergone complex and intricate histories, with shifts in control from local lords (apparently the Da Porcari family), to the Empire, the Diocese, Lucca, and Florence, yet they have always formed a unified whole. The local sense of identity — a rightful feeling of belonging — has historically set Pariana against Villa Basilica, which has always been the administrative center of the area both politically and religiously. However, what is referred to as the “plebanate of Villa” in various documents actually represents an inseparable and long-lasting unity of the four churches and villages, the result of a strong and ancient popular custom of staying together.

This unity was so strong that, with just these four localities, they formed a plebanate territory — unlike other plebanates, which were usually much broader and sometimes variable. In the excerpt from the following document — the 1196 deed in which Emperor Henry VI granted the fief to Glandone, a member of a wealthy notary family connected to the Empire — Pariana, together with Villa Basilica, Colognora, and Boveglio, composed the “Plebanate of Villa Bassirica,” and it would continue to be cited as such in all subsequent documents.

ASL, DIPLOMATIC DOCUMENT, TARPEA: HENRY VI GRANTS PARIANA, ALONG WITH VILLA, COLOGNORA, AND BOVEGLIO, IN FEUD TO THE LUCCHESE CITIZEN GLANDONE.

Research highlights that Lucca, first and foremost, had a strong interest in maintaining control over this territory, and secondly, that its strategic importance led the city of the Volto Santo to keep the border complex formed by the four communities of Villa Basilica, Pariana, Boveglio, and Colognora united and cohesive.

This attention from Lucca — then a major commercial, productive, and political hub in Italy — is further proof of the role this territory played. The truly strategic location was naturally the Pizzorne Plateau, a natural pass to and from Lucca, Pistoia, and Florence.

It was precisely this condition that led to the birth and development of Pariana as we know it (a fortress and a comune governed by a podestà): Pariana was the Apennine gateway to the heart of Tuscany, as demonstrated by the grandeur — unmatched by any other road structure — of the Ponte alla Maddalena.